“Brilliant – this writer has mastered the essay form and this one really packs a punch.” Vicky Spratt, author, housing correspondent for The i, and Orwell Youth Prize 2024 judge

“When you come back to England from any foreign country, you have immediately the sensation of breathing a different air. Even in the first few minutes dozens of small things conspire to give you this feeling.” So begins George Orwell in his essay The Lion and the Unicorn, written in 1941 [1]. But where is the British nation now? (Not unusually, as Orwell admits, he is conflating England and Britain. [2]

It might help if we first define Britishness. The writer of the Docu-Drama Mr Bates vs the Post Office, Gwyneth Hughes, suggested of the sub-postmasters depicted, ”They’re so British, aren’t they? Everybody involved is British to the core,” [3] depicting their nationality as linked to an ability to discern injustice. It seems strange to suggest that the thoughts and feelings of over sixty million vastly different people, many of whom profoundly dislike each other, can be boiled down to a shared personality. How would you summarise Britain?

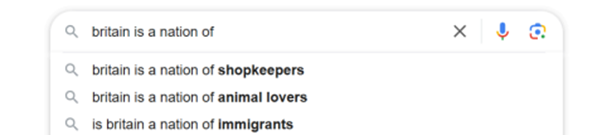

In 1941 Orwell called Britain a nation of “shopkeepers at war.” [4] Let’s consult our modern-day oracle: Google. Try typing in Britain is a nation of…

The first suggestion [5] I received was shopkeepers. Proof of Orwell’s description still being relevant? Just look at all our boarded-up shops and consider how reliant we are on online shopping. [6]

To define our Britishness we must look at another suggestion: Immigrants. [7] Britain has become far more multicultural than in Orwell’s lifetime. What we derive from foreign arrivals is integral to our culture and national identity. Chicken tikka masala, a dish invented in Britain by immigrants, is oft-cited as Britain’s national dish. [8] [9] And which of us could do without the Italian pizza or pasta? Along with the cuisines they bring, immigrants are central to our public consciousness. The Somali-born Mo Farah’s Olympic triumphs won him BBC Sports Personality of the Year. Rita Ora and Dua Lipa, both from Kosovan refugee families, are just some of the immigrant British singers dominating our charts in recent years. Let’s not forget how crucial immigrants are to staffing our NHS and care systems. Twenty-first-century Britain is a multicultural, inclusive country where anyone can succeed. Right?

Apparently not. In November 2023, the Times published an article by Matthew Syed, headlined “Migration is being used to enfeeble us,” [10] suggesting that immigration was being driven by “an autocratic axis of nations,” seeking to weaken Britain.

“Immigration is destroying the British economy,” according to a recent Telegraph article, ‘Immigration is destroying the British economy’. [11] Spare a thought then for Luxembourg, which has 3.5 times the level of foreign-born nationals than the UK. [12] Luxembourg’s GDP per capita of £118,919 [13] warns Britain (£37,452 [14]) just what a menace immigration is to a nation.

With University College London research showing that immigration benefits the British economy, [15] why do 63% of Brits believe immigration is too high? [16] Orwell suggests that “the famous ‘insularity’ and ‘xenophobia’ of the English is far stronger in the working class than in the bourgeoisie.” [17] Indeed, in the 2016 EU referendum, Leave received its highest support in working-class, deprived areas. [18] The belief that immigration is to blame for the lack of opportunities and increased anti-social behaviour in their areas is pervasive.

So who benefits from this belief?

As usual, it’s the rich. Orwell suggested that “there is not one paper in England that can be straight-forwardly bribed with hard cash,” [19] This was optimistic, and rather than bribery, nowadays billionaires simply buy newspapers, allowing them to control the message the public is given. [20] They can also use their riches to leverage influence over politicians and parties. [21] It suits them if immigration is blamed for our societal ills. No need to mention how the rich benefit from the austerity policies and neoliberalism which entrench inequality. [22]

Mass immigration is not something new. It did not start with our entry to the EU or the arrival of the Empire Windrush. [23]

Orwell’s Britain was also shaped by mass migration. Much of it can be traced to the instability caused by our slave trade [24] and our empire. [25] When British immigrants are accused of taking away opportunities from others, they can rightfully argue, “We are here because you were there.” [26]

But historically, many Brits have left the country to seek new opportunities or escape the conflict and poverty that permeated much of the British Isles. [27] A decline in emigration from the UK in recent decades, with rising living standards [28] giving less reason to emigrate (at least until recently), is a success story. Britain has entered a rare period in which there are consistently more people moving to Britain than leaving it. [29] Why should that be a bad thing?

British emigrants Andrew Carnegie and John Muir’s successes in America are justifiably celebrated in Britain. So why the struggle with accepting those born elsewhere as a key part of the British nation? (Exceptions are made for those whose families are white and rich, eg New York-born Boris Johnson.)

Frankly, we need to realise that Britain is not a medieval castle to protect.

An old-fashioned view of other nationalities is as strong now as when Orwell bemoaned “the dislike which nearly all foreigners feel for our national way of life.” [30] But his idea of a malevolent agenda against Britain is neither true nor useful as an excuse. Relative to our size and economy, Britain still has an outsized role in the cultural world, the UN and NATO. These roles are largely based on our historic power and will diminish as the world decolonises. [31]

Our island location once gave us an advantage in seafaring and by extension wealth-building and slave trading.

But as maritime dominance has proved impossible to maintain [32], we are perhaps a little isolated on our small island.

Dean Acheson’s suggestion in the 60s that “Britain has lost an empire but not yet found a role” [33] still seems relevant today. Indeed, 32% of Brits think our empire is something to be proud of, one of the highest among the imperial nations polled. [34] We built our identities, values, and economy on a world where we could exploit the resources and people of other nations. When that rotten edifice crumbled to the ground we were lost. [35] Britain needs to define itself by a new future, not with celebrations of our morally clouded past.

Orwell suggested, “England is outside of European culture.” [36] And even before Brexit, many in Britain were ambivalent at the idea of other countries influencing us. [37] Our politicians’ reluctance to integrate further into Europe and constant badmouthing of “European bureaucrats” [38] shockingly led to us being sidelined! [39] This first cycle of self-harm completed, rather than admitting that our jingoism and old-fashioned mindset had created needless damage and seeking to repair it, Britain doubled down. In the EU referendum, we were told “We don’t need the EU anyway.” [40] All that was needed to miraculously rescue the country was to “Believe in Britain,” [41] and “Bring back the Blitz Spirit!” [42] If only life were that easy. Pulling yourself out of the world’s largest common market may have felt like the shock therapy Britain needed, but according to the impartial public body, the Office for Budget Responsibility, Brexit has harmed Britain’s trade and industries. [43]

So what of our future? Orwell struck a note of optimism in concluding, ”The tendency of advanced capitalism has been to enlarge the middle class and not to wipe it out as it once seemed likely to do.” His optimism seemed to be warranted after the war. In his final years, Orwell witnessed the creation of the NHS and the Welfare State. There was hope that a more peaceful, fairer Britain would emerge from the ashes of the war. Orwell passed away in 1950 before the full flourishing of these ideals.

Never mind, after Thatcherism and austerity, our welfare state has been well and truly shaken up. Let’s hope Orwell has enough space to turn in his grave.

In 2024 we have a country where young people can’t get housing, [44] poverty is rising, [45] and our NHS is on the verge of collapse. [46]

So Orwell’s final lines in “The Lion and the Unicorn,” still seem apt, “We must add to our heritage or lose it, we must grow greater or grow less, we must go forward or backwards.” [47]

It’s time to challenge a political class that tells us that austerity is necessary, that cutting immigration is the key to solving our problems. There’s a generation of young people who want to change things for the better, to have a country to be proud of. We have to keep believing that’s possible.

[1] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

[2] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius ( London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

[3] Radio Times Awards Issue Radio Times,10-16th February 2024, pg7

[4] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

[5] See Appendix

[6] M. Sweeney, The Guardian, John Lewis boss calls for royal commission to save UK high streets | Wilko | The Guardian Acessed 11th September 2023

[7] See Apendix

[8] R.cook, The Guardian, Robin Cook’s chicken tikka masala speech | Race | The Guardian Acessed 9th November 2023

[9] The Spice Odyssey Chicken Tikka Masala | Britain’s National Dish | Butter Chicken | Murgh Makhani — The Spice Odyssey Acessed March 3rd 2024

[10] M.Syed,The Times Migration is being used to enfeeble us, so it’s clear what we have to do (thetimes.co.uk) Acessed March 3rd 2024

[11] P. Ullman, The Telegraph Immigration is destroying the British economy (telegraph.co.uk) Acessed March 3rd 2024

[12] The Statistics PortalGeographical distribution of immigrants – Statistics Portal – Luxembourg (public.lu) Acessed March 3rd 2024

[13] The World Bank GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) – Luxembourg | Data (worldbank.org) Accessed 4th march 2024

[14] The World Bank GDP per capita (current US$) – United Kingdom | Data (worldbank.org) Accessed 4th March 2024

[15] C. Dustmann, T. FrattiniThe Fiscal Effects of Immigration to the UK | UCL Department of Economics – UCL – University College London Accessed 4th March 2024

[16] Yougov Do Brits think that immigration has been too high or low in the last 10 years? (yougov.co.uk) Acessed 5th March 2024

[17] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius ( London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

[18] M. Goodwin, O. Heath, Joseph Rowntree FoundationBrexit vote explained: poverty, low skills and lack of opportunities | Joseph Rowntree Foundation (jrf.org.uk) Date accessed 21st April 2024

[19] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

[20] R. Neate, The Guardian‘Extra level of power’: billionaires who have bought up the media | The super-rich | The Guardian accessed 5th April 2024

[21] R. Merrick, The Independent Conservatives branded ‘party of billionaires’ as one-third of UK’s richest people donate to Tories | The Independent | The Independent accessed 5th April 2024

[22] K. Farnsworth, Z. Irving, London School of Economics Austerity politics, global neoliberalism, and the official discourse within the IMF | British Politics and Policy at LSE accessed 5th April 2024

[23] C. Grant, English HeritageThe Story of Windrush | English Heritage (english-heritage.org.uk) accessed 5th April 2024

[24] The Palgrave Handbook of South–South Migration and Inequality, Palgrave MacMillian The Enduring Impacts of Slavery: A Historical Perspective on South–South Migration | SpringerLink accessed 5th April 2024

[25] M. Greenwood, Manchester University Global Social Challenges | The Impact of the Past: How British Colonialism Affects the Modern World (manchester.ac.uk) accessed 5th April 2024

[26] Ambalavaner Sivanandan, Quoted in Empireland by S. Sanghera, (Penguin, London, 2021)

[27] The Migration Museum Migration MuseumThe last great exodus from Britain? – Migration Museum accessed 5th April 2024

[28] C.H FeinsteinNational Income, Expenditure and Output of the United Kingdom. 1855-1955. Studies in the National Income and Expenditure of the United Kingdom, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1972)

[29] Full Fact What’s happened to migration since 2010? – Full Fact accessed 5th April 2024

[30] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

[31] T. Janoski, British and French political institutions and the patterning of decolonization British and French political institutions and the patterning of decolonization (Chapter 11) – The Comparative Political Economy of the Welfare State (cambridge.org) Date Acessed 11th April 2024

[32] D. Axe, Reuters Commentary: What the U.S. should learn from Britain’s dying navy | Reuters Date Acessed 11th April 2024

[33] R. Deliperi, Dean Acheson’s Observation of Great Britain in 1962 Dean Acheson’s Observation of Great Britain in 1962 (e-ir.info) Date Acessed 11th April 2024

[34] M. Smith, Yougov How unique are British attitudes to empire? | YouGov accessed 1st May 2024

[35] Paul Beaumont Brexit, Retrotopia and the perils of post-colonial delusions, Global Affairs, 2017

[36] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

[37] M. Skey, London School of EconomicsBritish attitudes towards Europe are being shaped by new ways of thinking about identity and place | British Politics and Policy at LSE acessed 1st May 2024

[38] British Euroscepticism as British Exceptionalism on JSTOR

[39] I, NGUYêN-DUY, Sovereignty and Europe – The British Perspective » L’Europe en Formation, 2012, issue 2

[40] D.Bertheksen, The Critic Britain is better off outside the Single Market | Derrick Berthelsen | The Critic Magazine accessed 1st May 2024

[41] S.Sweeney, Brexit Institute Believe in Britain: The Simple Message that Won Brexit Still Works Wonders for Boris Johnson – Brexit Institute (dcubrexitinstitute.eu) date acessed 3th April 2024

[42] Channel 4-Youtube (2336) Brexit Blitz spirit: Why does it always come back to the war? – YouTube date acessed 3th April 2024

[43] Office for Budget Responsibility Brexit analysis – Office for Budget Responsibility (obr.uk)

[44] DePaul Depaul UK – Generation rent: Young people and the housing crisis date accessed 11th April 2024

[45] Joseph Rowntree Foundation UK Poverty 2024: The essential guide to understanding poverty in the UK | Joseph Rowntree Foundation (jrf.org.uk) Date Acessed 23rd January 2024

[46] National Centre for Social Research Public attitudes to the NHS and social care | National Centre for Social Research (natcen.ac.uk) Accessed 27 March 2024

[47] G. Orwell The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius (London, Secker and Warburg:1941)

Appendix- additional sources consulted

Immigration is destroying the British economy (telegraph.co.uk)

UK economy is addicted to immigration but there is long-term treatment | Larry Elliott | The Guardian

White British school children ‘could be a minority within 40 years’, study claims | Daily Mail Online

Dave Vetter on X: “The Sunday Times today published in its opinion pages what appears to be a variant of Great Replacement theory, the conspiracist fantasy that lies at the heart of several extreme right-wing ideologies🧵 https://t.co/CCzmSaYnmm” / X

Mo Farah’s experience highlights need for safe routes for all asylum seekers (bestforbritain.org)

Stir-fry now Britain’s most popular foreign dish – Mirror Online

About — Very British Problems

What other lobbying scandals have there been in British politics? | Lobbying | The Guardian