We asked four professional writers to create resources to help guide entrants through the process of researching, finding a form, starting to write and responding to feedback on an entry to the Orwell Youth Prize.

Who am I? (part 1)

I’ve always done lots of writing of different kinds, though what I’ve ended up doing most is poems. I started writing poetry in my mid-teens because I didn’t know anyone else who was doing it. Also, I couldn’t play any instruments and I’d read somewhere that poems were like song lyrics without the music.

I’ve always done lots of writing of different kinds, though what I’ve ended up doing most is poems. I started writing poetry in my mid-teens because I didn’t know anyone else who was doing it. Also, I couldn’t play any instruments and I’d read somewhere that poems were like song lyrics without the music.

Since then, alongside writing poems (and working), I’ve written book reviews and essays. They access different parts of my brain: a poem can be justified by sound or feeling; an essay will be judged on its argument. But I like going between them. When I get frustrated with a poem, I can walk next door (in my brain) and write an essay. In doing that, something might get dislodged in the poem.

The first book I published was a short non-fiction book (or long essay) called Mixed-Race Superman, which circled around race, heroism, masculinity, and the limits of speech to affect political change. It came about by chance – as in, I wasn’t planning to write it – but its form emerged from the process of writing; it almost made the writing of it necessary.

What is form?

It makes sense to look for analogies in other art forms (that word again): in music, for example, form might be the rhythm or time signature of a piece; in art, form might refer to the lines and shapes an artist draws on the page before adding colour and shade.

Form could, in musical terms, be described as the rhythm animating a piece of writing – the flow that makes the words sound good (‘right’) and keeps the reader’s eye moving down the page.

In painterly terms, it could be the shape of a piece of writing, whether short/long sentences and paragraphs, lots of punctuation, or (in the case of poems) lines, stanzas, even particular shapes into which the text has been fitted.

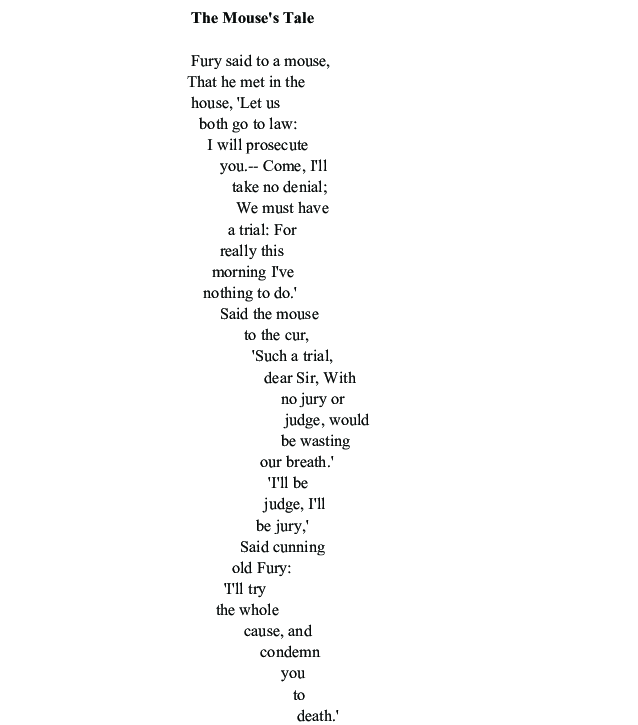

The most famous example of shape-based writing – also known as concrete poetry – probably comes from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where Alice imagines a mouse telling a tale shaped like a mouse’s tail and we see the text curl down the page in that very shape, a perfect fusion of form and…

…she kept on puzzling about it while the Mouse was speaking, so that her idea of the tale was something like this –

Form and…?

Form on its own doesn’t make much sense (or about as much sense as sense does without sound). Form exists as one half of a duo. As day conjures night, form brings up the shadow of content.

But what is content? Content is usually synonymous with subject matter. Your content might be – on any given day – the taste of Lilt, the government’s reliance on foodbanks, the life cycle of the eel. Form is how this subject comes to appear on the page.

Content is the dough, and form is the kitchen appliance that turns it into spaghetti. But that doesn’t quite capture it. Because dough is itself an already carefully mixed and kneaded ‘form’. Form and content, likewise, are an inseparable yin-and-yang duo; you can’t think of one without the other.

Examples?

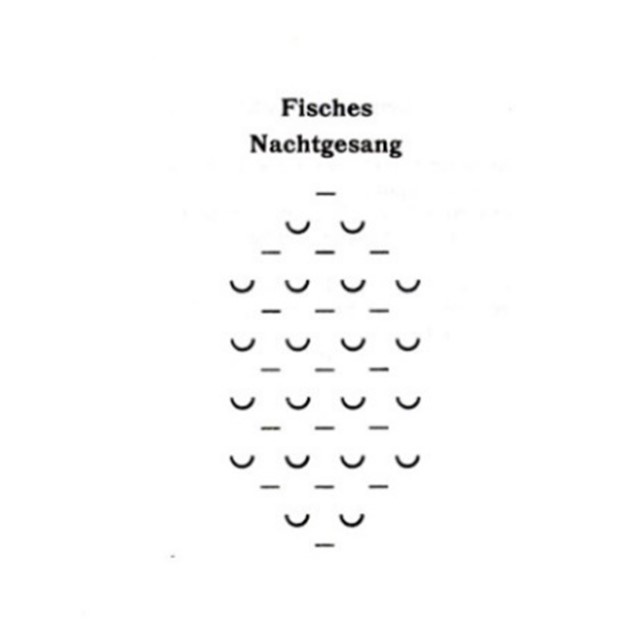

Let’s take two examples which might, like the mouse’s tale, be called perfect unions of form and content.

- In the 1730s, Alexander Pope wrote this two-line poem (a couplet) and had it engraved on the collar of a dog which he gave to the Prince of Wales:

I am his highness’s dog at Kew;

Pray tell me, sir, whose dog are you?

- The German poet Christian Morgenstern wrote this poem well over a century ago, whose title translates as ‘Fish’s Night Song’:

But do you agree that these two poems are especially pleasing combinations of form and content? If so, why? And if not, how could you do it better?

A challenge:

Write your own example of form and content perfectly combined. It could be a text to be written on the side of a helicopter, tattooed on the chest of a famous actor, or inscribed on a single sheaf of grass. Let your imagination wander.

Forms around us

In her preface to Frankenstein, Mary Shelley writes that ‘invention, it must be humbly admitted, does not consist in creating out of void, but out of chaos.’ Chaos might be another name for content without form.

We can’t help but impose forms on the world, thinking ‘tree’ or ‘that feels like cotton’ or ‘that dog looks happy’. Invention in writing isn’t so different. It begins with the same heightened awareness of form, of the forms already around us.

In this mood of heightened awareness, the premonition of form meets us everywhere: in the pattern of bubbles in a soft drink, in crowds flowing out of the station, in clouds. We can’t avoid it.

And maybe the point of writing, as Mary Shelley argues, isn’t to invent something out of nothing; it’s to recreate that feeling when several chaotic wisps of cloud briefly combine to form the shape of a happy dog.

Who am I? (part 2)

Writing is often reduced to its content or subject matter. It’ll always be about something (a kidnapped dog in Alaska, a star-crossed couple in Italy, etc.).

But much of the time writing starts with something harder to pin down: the search for a form. This might be no more than a rhythm or a shape on the page. Form doesn’t hold content like a shell contains a nut. Form, like a satellite dish, allows us to reach those dark and faraway places we wouldn’t know existed otherwise.

A challenge:

I want you to think about how you would answer the question ‘Who am I?’ Try to follow the intuition of form. For example, what you write could take the form of a pair of trainers, an astrological chart, or a series of instructions (to get somewhere or make a dish). Whatever the case, let the rhythm and line carry the form and take you somewhere unexpected.

BONUS ACTIVITY! Sleepy time with James Joyce

The Irish writer James Joyce was someone for whom form was the whole point of writing. From the late 1920s to the end of the 1930s – the last decade of his life – he wrestled with a book in which, as his friend Samuel Beckett put it, ‘form is content, content is form.’ Beckett would go on to say: ‘His writing is not about something; it is that something itself… When the sense is sleep, the words go to sleep…’

But what do sleeping words look like? This is Joyce’s attempt to write in a language that doesn’t describe sleep but feels sleepy, from Finnegans Wake (1939):

Can’t hear with the waters of. The chittering waters of. Flittering bats, fieldmice bawk talk. Ho! Are you not gone ahome? What Thom Malone? Can’t hear with bawk of bats, all thim liffeying waters of. Ho, talk save us! My foos won’t moos. I feel as old as yonder elm.

What makes these words sleepy? The way the sentences trail off, the preponderance of sound over sense, the warped allusion to nursery rhyme, song or proverb?

A challenge:

Fill a page with a piece of writing in which ‘the sense is sleep, the words go to sleep.’ Be as imaginative with the page as you can. Draw on anything that makes you think of sleep and think about how to make the words themselves feel sleepy.

Thank you for reading this resource. We hope you enjoyed it and that it comes in useful as you write your entry to the Orwell Youth Prize! If you have any feedback on our resources, please email info@orwellfoundation.com.

Will Harris is a London-based writer. His debut poetry book RENDANG (2020) was a Poetry Book Society Choice, shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize and won the Forward Prize for Best First Collection. His second book of poems, Brother Poem, was published by Granta in the UK and by Wesleyan in the US in March 2023.

The commission of these resources was supported using public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England as part of the Orwell Foundation’s Regional Hubs project.